Which is worse, too little or too much?

I ask the question because I’m in the middle of a script project that has me swamped in potential content. It’s a 45 minute documentary covering a fair sweep of history. The client has provided three books, about a gigabyte of archived historic materials, and 600 pages of interview transcripts. I feel like Ken Burns, except — unlike Burns — I don’t have infinite time and money to plow through the project.

The point of this is that over-researching costs time and money all the way through a project, and is usually a function of a lack of understanding at the outset of what the final product was going to be.

The researchers working on this documentary — which is going to be killer, by the way — threw a wide net. I’m sure it was a great project for them; they found all kinds of cool things that ultimately have nothing to do with this project.

The interviewers had long, wandering conversations with their subjects that cost a lot of crew time at about $500 an hour. The transcripts cost a couple of bucks a minute and make great reading, but provide remarkably little relevant material. For example, I just got finished reading through an 18-page transcript that was absolutely fascinating, but provided all of one sound bite.

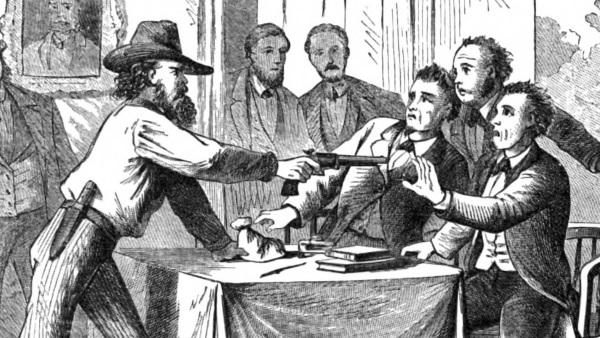

And then there is the writing. The more material the writer has to wade through and assimilate, the longer it takes to pare things down into a script. And, when the draft is finished, a vast mass of material increases the odds that someone up along the line will want included something the writer chose to leave out — a favorite moment from an interview or story from a news article from 1934. (Nobody gets to know the material as well as the writer, who is responsible for the whole scope of information to be considered. People who are familiar only with part of the material often latch-onto things that may be terrific but didn’t make the final cut.) That leads to shootouts at unnecessarily long script meetings, conference calls, and hurt feelings that take more time and money.

It costs time and money to create a solid outline of a story before going into production, but that is an investment that will save time and money throughout the production. A solid roadmap of the story to be told prevents getting getting distracted when a bunny runs across the trail.

There’s an argument to be made — and I’ve certainly made it — that writing the story before conducting the research forecloses the possibility of happy accidents — the discovery of things unknown that could elevate the production. That is, to a degree, true. But it’s also true that everyone (except Ken Burns) is working with limited time and money. Having a solid outline of the story before going far down the road doesn’t make impossible the inclusion of previously unknown material; it just raises the bar for its inclusion. There is always a place for the big, wonderful thing that comes out of nowhere. Staying on-point through a production just makes it harder for small things that make little difference to disrupt the production process.

There is a saying that “politics ain’t beanbag”. It is equally true that professional creative ain’t playtime. Hunter Thompson, responding to someone who suggested that writing must be a fun way to make a living, pointed out that nothing done for money is fun. “Old whores don’t do much giggling,” Thompson said. The job of a professional is to get things done. It is not to create great art (unless you’re Ken Burns) and it is not to exercise your creative muscles. It is to get to a desired outcome as quickly and efficiently as possible, and sometimes that means everyone has to work hard to do less.